Most of What You Hear about Forest Health & Wildfires is Wrong

Water is life. We know that, but our forest policy & practices do not reflect this basic reality.

Water puts out fires. We know that, too, but public policy goes in the opposite direction.

A healthy forest holds more water than a degraded forest. It holds water in the soil, the plants and the organic matter. But we degrade our forests with too much logging and “thinning” causing them to dry out and become more flammable.

At every turn, we allow the timber industry to practice logging and “tree thinning,” which dries out our forests, causing them to die of thirst and making them more likely to burn in such a way as to put people, buildings and communities at greater risk of wildfire.

A few truth-tellers stand in the way of the false narratives that cause our forests to dry out and become more flammable. This includes Dr. Chad Hanson and his colleagues at the John Muir Project, who have given us “Fuel Reduction” Logging Increases Wildfire Intensity, one of the most valuable resources we have to counter the false narratives that threaten our forests.

Here's why I say it is valuable.

False Narrative: Fuel Buildup

The false narrative is that fire suppression has been so successful in the last hundred years, resulting in fuel buildup. This fuel buildup has caused wildfires to burn out of control with increased frequency. Naturally, the solution is to reduce the fuel, via “thinning” (i.e., logging) so as to reduce the intensity of wildfires.

This narrative is good for the timber industry, because they get to extract timber for profit.

But what if thinning and logging actually make fires spread faster and burn hotter, posing a greater threat to people, buildings and communities?

The John Muir project has put together this fact sheet containing scientific evidence that commercial thinning and post-fire logging make wildfires spread faster and/or burn more severely.

Consider these questions, with corresponding references from the fact sheet.

Does timber harvest increase or decrease fire severity?

“Timber harvest, through its effects on forest structure, local microclimate, and fuel accumulation, has increased fire severity more than any other recent human activity.” (SNEP, 1996)

How does timber harvest affect the “local microclimate”? When you harvest timber, you expose the floor of the forest to sunlight, thus drying out the soil, as well as the grasses, the leaves and the twigs lying on the forest floor. Also, the forest floor experiences more wind, which has a drying effect.

This makes the forest floor more flammable and makes fires spread faster. And then when the fire does occur, there are fewer trees to impede the wind. Greater winds fan the flames, making fires spread faster and burn hotter.

Do we need to practice “salvage logging,” i.e., extracting the timber of dead trees after a fire?

“[S]ome argue that salvage logging is needed because of the perceived increased likelihood that an area may reburn. It is the fine fuels that carry fire, not the large dead woody material. We are aware of no evidence supporting the contention that leaving large dead woody material significantly increases the probability of reburn.” (Beschta, 1995)

In fact, dead wood becomes increasingly porous over time. It absorbs rainfall, becoming wetter and less flammable. Dead, wet logs then share their moisture with the surrounding soil and plants, increasing plant growth.

Growing plants then transfer carbon from the air to the ground through photosynthesis. Carbon-rich soil then absorbs more rainfall, making the ground hold more water and so on, in a virtuous cycle.

Note well: It is the large, woody material that is the most valuable to the timber industry. And yet, the large, woody material is the least flammable.

Assuming fires burn hotter and faster with fuel that is warm and dry, how does logging affect the fuel in the forest?

When moving from open forest areas, resulting from logging, and into dense forests with high canopy cover, “there is generally a decrease in daytime summer temperatures but an increase in humidity…” (Chen, 1999)

A dense forest is a cooler, more moist forest that is less flammable and less likely to experience high winds that fan the flames.

Can thinning be justified by claiming decreased “tree mortality”?

The industry wants us to believe that thinning results in a lower rate of tree mortality. But they typically don’t count the tree mortality resulting from logging. So Hanson, et. al. studied “combined tree mortality, i.e., the tree mortality resulting from both logging and fire.

“In all seven sites, combined mortality [thinning and fire] was higher in thinned than in unthinned units. In six of seven sites, fire-induced mortality was higher in thinned than in unthinned units…Mechanical thinning increased fire severity on the sites currently available for study on national forests of the Sierra Nevada.” (Hanson, 2006)

Isn’t it interesting that when reporting on “tree mortality” due to fire, they don’t also consider the tree mortality due to logging? If they did, the logging would not seem to be so beneficial to the trees.

Why is this important?

Pro-logging propaganda pervades the media and dominates in the halls of Congress. Pro-logging propaganda claims to be scientific and, of course, in the public interest.

They want is to think that commercial “thinning” results in a healthy forest and reduced danger of fire.

But what if the opposite is true? And what if you and I, average citizens with no profit motive and with no political career to protect, are the only thing protecting our forests from bad public policy funded by a profit-motivated industry?

This fact sheet is a valuable resource for anyone who wants to help us take back the narrative and protect our forests from industry and bad public policy.

REFERENCES

Beschta, R.L.; Frissell, C.A.; Gresswell, R.; Hauer, R.; Karr, J.R.; Minshall, G.W.; Perry, D.A.; Rhodes, J.J. 1995. Wildfire and salvage logging. Eugene, OR: Pacific Rivers Council.

Chen, J., et al. (co-authored by U.S. Forest Service). 1999. Microclimate in forest ecosystem and landscape ecology: Variations in local climate can be used to monitor and compare the effects of different management regimes. BioScience 49: 288–297.

Hanson, C.T., Odion, D.C. 2006. Fire Severity in mechanically thinned versus unthinned forests of the Sierra Nevada, California. In: Proceedings of the 3rd International Fire Ecology and Management Congress, November 13-17, 2006, San Diego, CA.

SNEP (co-authored by U.S. Forest Service). 1996. Sierra Nevada Ecosystem Project, Final Report to Congress: Status of the Sierra Nevada. Vol. I: Assessment summaries and management strategies. Davis, CA: University of California, Davis, Center for Water and Wildland Resources:

*******

Virtually absent from the public discourse is an understanding of how our forests create healthy water cycles.

From evaporation, to condensation to cloud formation to precipitation, our forests drive healthy water cycles.

And our forests depend upon these same water cycles.

As it interacts with water, a forest becomes a sponge, a water filter, an air filter and so much more!

This is yet another reason to stand against the timber industry’s love affair with commercial thinning, as well as all the burning and spraying, which they do for commercial reasons, but which degrade our forests.

As a result logging is one of the biggest emitters of carbon in the world, and the United States ranks at or near the top of the world in logging.

How can we stop this trend or at least slow it down?

Some would say awareness is key.

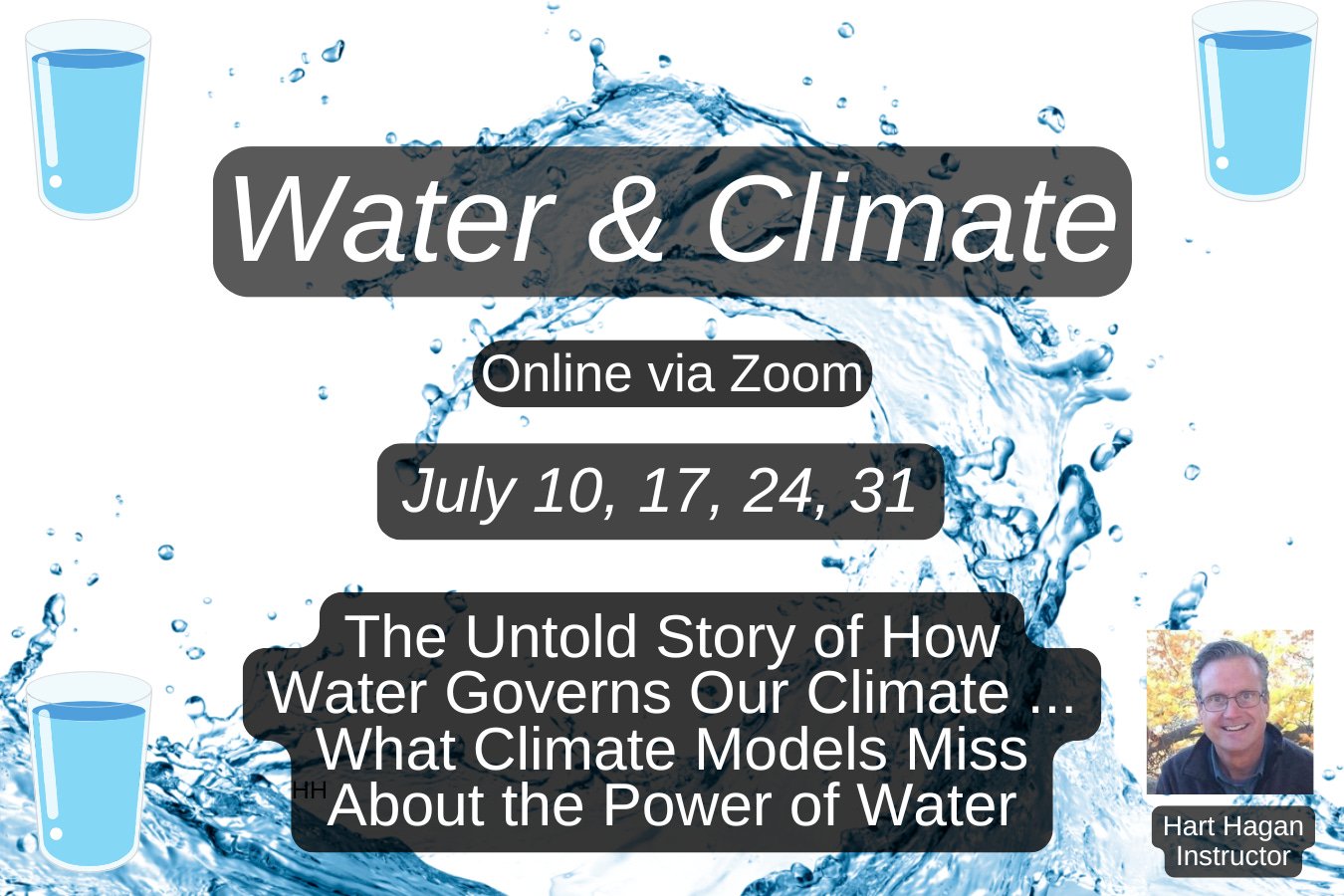

The Water & Climate course exists to enhance our awareness and deepen our understanding that water is life, and water is one of the biggest factors in our climate.

Check out the Water & Climate course, starting in July.